The Frozen Zoo® is nothing short of a treasury of life on Earth. This indispensable resource, part of our Wildlife Biodiversity Bank, holds frozen living cells from more than 11,500 individual animals of 1,300 species or subspecies, many of them endangered or even extinct. Within these microscopic samples lies the extraordinary potential to reintroduce valuable genetic diversity into wildlife populations, safeguarding species for generations to come.

As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Frozen Zoo, we reflect on its remarkable history and the groundbreaking achievements it has made possible. It is and always has been an unparalleled tool for shaping the future of wildlife conservation and inspiring hope for species everywhere—and it will continue to pave the way in its next 50 years and beyond.

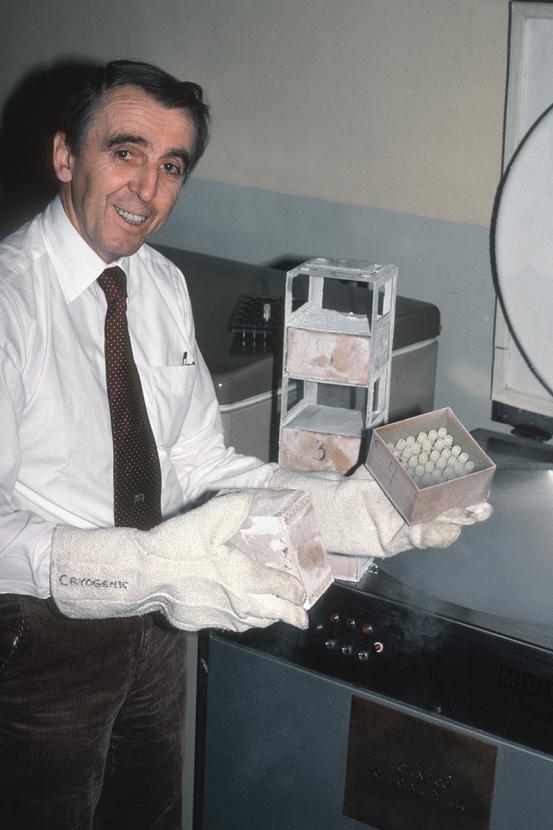

It all started with a visionary idea from Dr. Kurt Benirschke, one that would change conservation science forever.

1975: A New Way Forward

It all started with a visionary idea. Dr. Kurt Benirschke, part of the San Diego Zoo’s research department, began freezing living cells from various animals with liquid nitrogen. Though the uses of these samples were unknown at the time, he often repeated his guiding principle: “You must collect things for reasons you don’t yet understand.” His simple yet profound foresight became the foundation of a revolutionary approach to species conservation.

Highlights:

- The first samples were saved to the Frozen Zoo.

- Dr. Benirschke brought on board Dr. Oliver Ryder, who is now our Kleberg Endowed Director of Conservation Genetics and a pivotal force in saving endangered species.

Arlene Kumamoto served as the Frozen Zoo’s first curator, helping shape the direction of this exciting new resource.

1976–1992: Growth and Innovation

The Frozen Zoo team wasted no time in broadening their operations. By embracing cutting-edge technology and hiring talented new staff, they capitalized on Dr. Benirschke’s dream of what wildlife conservation could achieve.

Highlights:

- Scientists first used polymerase chain reactions (PCR) to amplify DNA, creating millions of copies from a single sample and thus exponentially increasing each one’s potential.

- Marlys Houck took a temporary position to research rhino chromosomes. Almost 40 years later, she’s now Elizabeth J.F. Williams Endowed Curator of the Frozen Zoo.

- The Frozen Zoo’s collection expanded rapidly, banking its 100th sample (from a lesser kudu), 500th sample (from a brown hyena), and 1,000th sample (from an Eastern bongo).

The inclusion of cells from a painted stork ushered in a new era of global bird conservation.

1993–2003: Furthering Their Reach

Different kinds of cells require different cryopreservation techniques. In its first two decades, the Frozen Zoo had the tools to bank cells from mammals. Scientific breakthroughs, however, soon unlocked new methods for preserving a wider range of wildlife. These advancements significantly increased the Frozen Zoo’s ability to protect species from around the world.

Highlights:

- The first avian cells were collected (from a painted stork), as were the first reptile cells (from a Pacific coast rattlesnake).

- A gaur, a wild bovine species, became the first endangered species cloned from cells preserved in the Frozen Zoo, demonstrating the technique’s capacity as a viable conservation tool.

- The Native Plant Gene Bank was established to preserve seeds and plant tissue, which couldn’t yet be frozen like animal samples. This new arm of the Wildlife Biodiversity Bank enabled teams to collect materials from the full spectrum of life on Earth.

- The 5,000th sample was banked (from a black-and-white lemur).

The 50,000-square-foot Beckman Center for Conservation Research has provided the Frozen Zoo a fertile homebase for its transformative operations.

2004–2018: A New Home

As the Frozen Zoo’s collection and capabilities grew, so did the need for a large, state-of-the-art facility to support them. Thanks to a landmark gift from the Beckman Foundation, the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center for Conservation Research opened at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park and provided an advanced new headquarters for the team’s efforts.

Highlights:

- The Conservation Education Lab was established, increasing the ability to share expertise with partners and student conservationists.

- The first amphibian cells (from an African clawed frog) and the first fish cells (from a rainbow trout) were banked.

- We established a cell line from the last living po‘ouli, a Hawaiian honeycreeper. It was the first viable material from an extinct species to be cryopreserved. Though the applications of this sample are still not yet known, it may one day provide valuable information about species conservation.

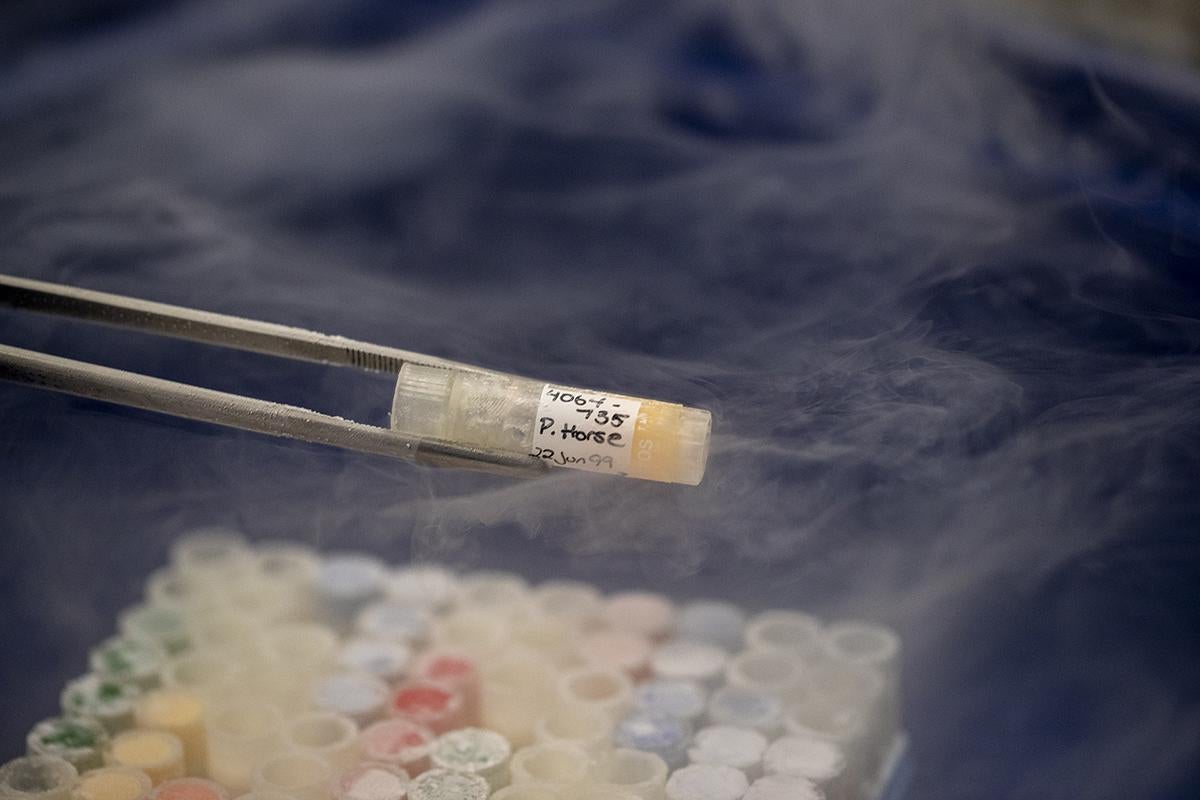

Through cloning, genetic diversity can be returned to populations, giving endangered species like Przewalski’s horses a promising future.

2019–2024: A Succession of Firsts

While innovations and milestones came often, each of them required hard work, dedication, and time. The investment was always worth it, however, and moments long in the making finally came to fruition.

Highlights:

- The first successfully cloned Przewalski’s horse was born, from cells preserved 40 years prior. Three years later, the second cloned Przewalski’s horse was born, the first time cloning successfully produced more than one individual of an endangered species. In a fitting tribute, the foals were named Kurt and Ollie, after Dr. Kurt Benirschke and Dr. Oliver Ryder.

- A cloned black-footed ferret successfully gave birth to two kits, the first instance of a cloned U.S. endangered species producing offspring.

- Teams devised a new way to cryopreserve embryos from Nuttall’s scrub oaks, an "exceptional species" that can't be banked like other plants. In the process, it became the first plant added to the Frozen Zoo.

- The 10,000th sample was banked (from a San Clemente loggerhead shrike).

In our next chapter, conservation leaders like Marlys Houck can collaborate with global scientists to help endangered species everywhere.

2025 and Beyond: The Next 50 Years

The Frozen Zoo has continually proven itself as an investment in the future of our planet. We are always looking toward biobanking’s next chapter, envisioning steps that will allow this irreplaceable repository to continue protecting and strengthening biodiversity everywhere.

Highlights:

- We will build on our decades of expertise and collaboration to lead the biobanking of all endangered species worldwide by 2075.

- The Beckman Center will grow in its role as an unprecedented hub of global biobanking and a unique venue of education and teamwork.

- In collaboration with partners in Hawaiʻi, Kenya, Peru, and Vietnam, we will help establish four new biobanks, empowering global scientists to protect an incredible array of native species.

With five decades of experience, passion, and unwavering commitment to protecting life on our planet, our Frozen Zoo team is more prepared than ever to tackle the conservation challenges of tomorrow. And together with partners around the world, the potential of our cryopreservation efforts is nearly limitless. 50 years in, the Frozen Zoo is just getting started.

Painted stork photo credit: Anastasia Korchagina/iStock/Getty Images Plus